Longest Careers in Cricket: Players Who Played for 20+ Years

In an age where cricket calendars are congested, workloads are carefully managed, and players rotate more than ever before, the idea of someone playing at the international level for over 20 years feels almost mythical. And yet, a select few have done it—not merely as passengers, but as pillars of their teams. Their names are etched among the longest careers in cricket, not just for time served, but for the impact made across eras.

Longevity in cricket is rarely linear. There are slumps, selections lost and regained, format shifts, injuries, and the sheer mental strain of staying hungry. Some players begin young and burn bright across formats. Others are late bloomers who stretch their twilight years with economy and purpose. What binds the longest careers together is an uncommon ability to adapt—not just technically, but psychologically.

This article doesn’t aim to celebrate longevity as a virtue in isolation. It looks deeper—at how these players responded to time itself. Some aged with grace. Others fought against it. All of them, in their own way, defied the rhythms that normally shorten cricketing lives.

Sachin Tendulkar – India (1989–2013)

If cricket had a human calendar, it would be measured in Sachin Tendulkar years. He debuted in 1989 at the age of 16, a prodigy thrown into a hostile debut series against Pakistan. When he retired in 2013, he had played in a world unrecognisable from the one he entered—from floppy hats and grainy broadcasts to DRS and T20 leagues.

In those 24 years, he became the most capped Test and ODI player in history. He made 100 international centuries, scored over 34,000 runs, and was often described as a cricketing constant in an ever-shifting world. But the numbers, as immense as they are, tell only part of the story.

Tendulkar’s career had phases. In the 1990s, he was India’s lone warrior in a fragile batting order. Aggressive, fearless, and often burdened with expectation. In the 2000s, he refined his game—less flourish, more control. His technique became tighter. His shot selection more selective. After tennis elbow nearly ended his career, he returned not diminished but more precise, more patient, more assured.

The secret to his longevity wasn’t just skill. It was intent. Tendulkar trained with monastic discipline, adjusted his technique as his body aged, and never stopped preparing like a newcomer. His ambition wasn’t just to score—it was to remain essential.

Even when India’s batting lineup was flooded with stars—Sehwag, Dravid, Laxman, Dhoni—Tendulkar remained its centre of gravity. And when he finally left, it felt like more than a retirement. It felt like the end of a cricketing era.

James Anderson – England (2003–present)

In a sport that often fetishises youth, James Anderson’s career has been a slow, methodical rebellion. When he debuted in 2003, he was raw, quick, and erratic—a reverse-swing hopeful with an exaggerated action and streaky control. Few imagined he’d still be opening the bowling in 2024, let alone at the top of his game.

Anderson didn’t just extend his career—he redefined what late-career excellence looks like. From 2010 onwards, he became a master of seam, swing, and subtlety. His wrist position tightened. His action was remodelled. He added patience to his armoury. The fire remained, but the chaos disappeared. He didn’t bowl to take wickets anymore—he bowled to ask relentless questions.

By 2024, Anderson had taken over 700 Test wickets, the most by any pace bowler in history. But even that doesn’t capture his value. In English conditions, he’s nearly unplayable. Overseas, once a vulnerability, became manageable. He kept evolving, outlasting generations of quicks with smarter spells and smarter bodies.

He’s bowled with Flintoff, Broad, Archer, Stokes—each part of different England eras. But Anderson has remained the common thread. He’s not just part of history. He is English Test history now.

Jacques Kallis – South Africa (1995–2014)

Kallis didn’t just last. He lasted while doing everything.

Batting in the top order, bowling fast-medium for long spells, and fielding in key positions—Kallis played over 500 international matches across formats. He retired with over 25,000 runs and nearly 600 wickets. His longevity isn’t just about time. It’s about carrying a workload most all-rounders eventually surrender to.

In his early years, Kallis was classical, composed, and sometimes criticised for being too cautious. But that caution made him South Africa’s most reliable insurance policy. He could bat for hours without fuss and still accelerate when needed. As bowlers aged and broke down, Kallis kept sending down overs with metronomic control.

What allowed him to endure was discipline without drama. His technique didn’t need constant revision. His body, rarely flashy, held up under pressure. He knew his game so well, he never needed to chase moments—he built them.

Few players have matched his consistency across formats. Fewer still have done it for two decades without significant dips. Kallis didn’t reinvent himself. He simply refined what already worked—and kept doing it longer than anyone expected.

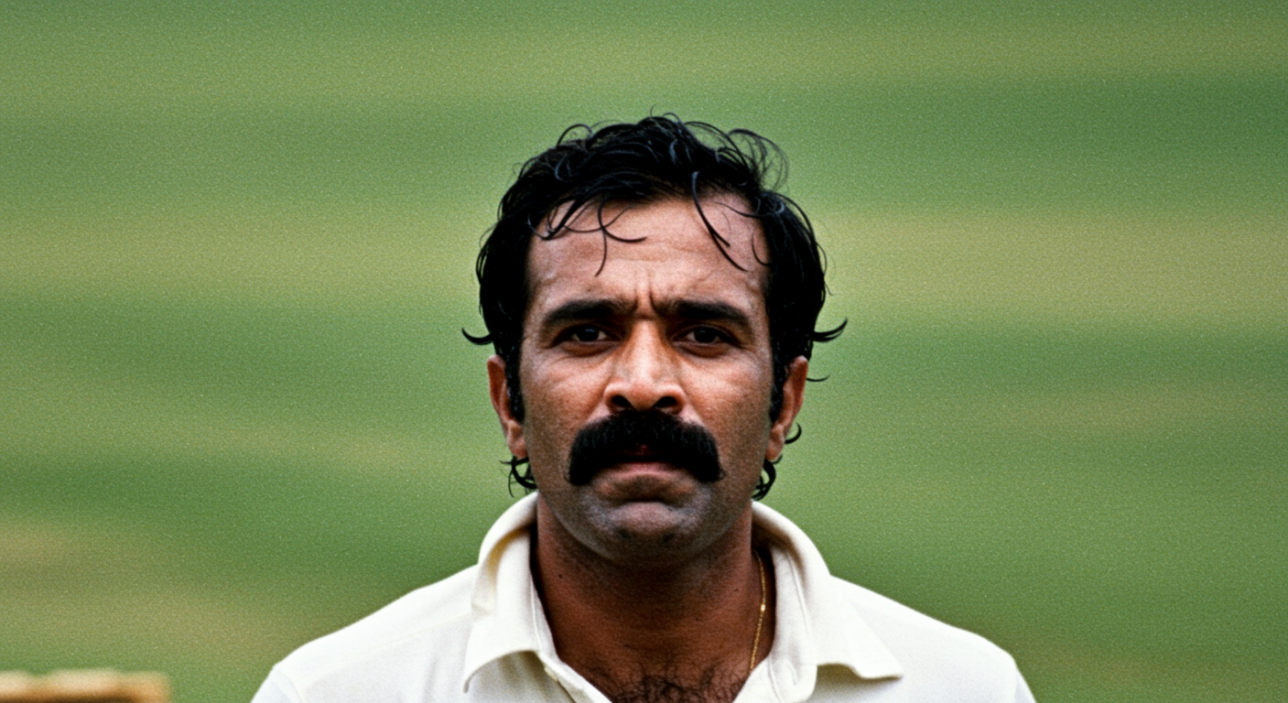

Shivnarine Chanderpaul – West Indies (1994–2015)

In a team often defined by flair, Chanderpaul was the bunker. A middle-order survivor who batted for the cause, not the cameras. His technique was unconventional—open stance, crab-like shuffle—but it worked. And it worked for over 20 years.

Chanderpaul’s longevity came not from dominance, but from resilience. He played during a turbulent period in West Indies cricket—constant change, declining standards, internal politics. Through it all, he kept making runs. Sometimes ugly. Often alone.

He scored over 11,000 Test runs, many of them in low-scoring matches where he was the only batter to survive. He batted with the tail. He batted through collapse. He batted not to entertain, but to endure. That made him less glamorous—but more essential.

While others came and went, Chanderpaul stayed. In whites, in maroon, at No. 5. Always ready. Always stubborn. And always just there—because someone had to be.

Javed Miandad – Pakistan (1975–1996)

Before longevity was tracked by fitness charts and workload stats, Javed Miandad gave it a different name—tenacity. His international career spanned over 21 years, beginning as a teenage prodigy and ending as a battle-hardened veteran. In between, he became Pakistan’s most cunning tactician and one of its most dependable run-makers.

Miandad’s greatness wasn’t built on aesthetics. His stance was unorthodox, and his footwork occasionally scrappy. But he read the game like few others—always one step ahead of the bowler, one second faster between the wickets, one sentence sharper in the sledging department.

He finished with over 16,000 international runs, but his value went beyond the scoreboard. Miandad was often Pakistan’s psychological edge. He stared down fast bowlers, unsettled spinners, and played mind games with captains. His ability to grind out tough innings—especially in hostile conditions—was central to Pakistan’s competitiveness through the ’80s and early ’90s.

When he returned for the 1996 World Cup at 38, well past his peak, it wasn’t for nostalgia. It was because Pakistan still believed he could make a difference. That belief, over two decades, says everything about the career he built.

Misbah-ul-Haq – Pakistan (2001–2017)

Misbah’s career is a story in two halves: a long wait, and an even longer finish. He made his Test debut at 27, disappeared, and then returned in his 30s to lead Pakistan through its most unstable period—post-spot fixing, post-crisis, and in exile from home.

Misbah didn’t just survive those years. He anchored them. He became Pakistan’s most successful Test captain, brought calm to chaos, and—almost silently—played on until the age of 43.

He didn’t have the flair of his predecessors, nor the mass appeal. But he was durable, clear-headed, and obsessed with discipline. He captained in over 50 Tests, often without fanfare, always with dignity. And his batting—slow, watchful, often criticised—proved time and again that stillness under pressure is a skill too.

He wasn’t built for 20-year careers. He made one happen by force of will.

Chris Gayle – West Indies (1999–2021)

In a sport often defined by discipline and restraint, Chris Gayle played cricket like a force of nature. For over 20 years, across formats and continents, he hit more sixes than anyone else, polarised more critics than most, and—despite it all—remained one of the most in-demand players in the world.

Gayle began as a classical opener with a high backlift and a broad bat face. But as T20s took over, he became something else entirely—a brand, a spectacle, a template. Few batters in history have hit the ball as hard, as high, and as often.

Yet beneath the bluster, Gayle had substance. He scored over 10,000 runs in both ODIs and T20s. He has two Test triple-centuries. He’s played over 450 international matches. And he’s carried West Indies on his back more than once.

What extended his career wasn’t consistency—it was relevance. In every new era of white-ball cricket, Gayle found a way to remain useful, dangerous, and, above all, entertaining.

His longevity came not from adaptability, but from stubborn excellence on his terms. He played how he wanted, when he wanted—and stayed longer than anyone thought he could.

Kapil Dev – India (1978–1994)

Kapil Dev’s career wasn’t supposed to last 16 years—let alone thrive for that long. He was a fast bowler from India, a country that had rarely produced quicks of repute. And yet, through sheer endurance and technical evolution, Kapil became the first Indian cricketer to truly embody the all-rounder ideal.

He bowled more than 27,000 deliveries in Tests alone. Took 434 wickets—then a world record. Scored over 5,000 runs. Won a World Cup as captain. And rarely missed a match. He didn’t rely on express pace or mystery movement. Instead, he stayed fit, kept his action simple, and always showed up.

Kapil’s legacy is defined as much by his longevity as by his landmarks. In a cricketing era that offered little scientific support to fast bowlers in the subcontinent, he kept going—without breaking down, without fading away. He set the tone for Indian cricketers to think beyond spin and survive beyond 30.

Imran Khan – Pakistan (1971–1992)

Imran Khan’s career had phases—young prodigy, fast-bowling spearhead, injury-prone technician, and finally, charismatic captain and national icon. Across 21 years, he went from a raw athlete to a statesman of the sport. And by the end, he had delivered Pakistan’s most prized possession: the 1992 World Cup.

His bowling action evolved to reduce stress on his body. His batting—once secondary—became increasingly central. As a captain, he was uncompromising and visionary, inspiring a generation of players through force of personality and tactical insight.

Imran’s longevity wasn’t just physical—it was political, cultural, and deeply personal. He played until 39 because he had unfinished business, and because Pakistan cricket needed him as much as he needed one final win.

Sanath Jayasuriya – Sri Lanka (1989–2011)

Few cricketers changed the way a format was played the way Sanath Jayasuriya did in the 1996 World Cup. His explosive starts at the top of the order—a blur of cuts, flicks and slashes—helped redefine what ODI batting could look like. But his career wasn’t built solely on that one tournament.

Jayasuriya played over 440 ODIs and 110 Tests. He took more than 300 international wickets. He captained his country. He returned to the national side in his 40s. And he played in a way that didn’t seem designed to last—but somehow did.

He outlived teammates, trends, and tactical eras, not because he evolved his game drastically—but because his base level was always just high enough. Even at 41, he could still take down a new ball attack with terrifying ease.

Longest Careers in Cricket: What It Takes to Stay

In a sport where careers are often measured by peaks, those who endure are playing a different game. Longevity in cricket isn’t about resisting age—it’s about negotiating with it. It means knowing when to adapt and when to stand firm. When to adjust your game, and when to double down on your strengths.

Players who cross the 20-year mark aren’t just freaks of fitness. They are students of the game’s shifting patterns. They survive new coaches, selection panels, formats, and philosophies. They embrace technology without becoming dependent on it. And they accept that greatness, over time, is less about highlights and more about turning up, again and again, at a high level.

What unites this list isn’t just longevity—it’s purpose. Tendulkar batted to carry a nation. Anderson bowls to master one more spell. Kallis delivered consistency under the radar. Jayasuriya lit up games in bursts. Imran returned to deliver a World Cup. And Chanderpaul? He just kept batting because someone had to.

In the end, a long career in cricket is a triumph over many things: expectation, criticism, injury, irrelevance. But above all, it’s a triumph over time itself. And that, in sport, may be the hardest thing of all.